AP Syllabus focus:

‘For solids with triangular cross sections, the base length is given as a function, students apply appropriate triangle area formulas, and integrate the area along the chosen axis.’

This subsubtopic explores how volumes of solids with triangular cross sections are determined by expressing cross-sectional dimensions from a base region and integrating accumulated triangular areas along a chosen axis.

Understanding Solids with Triangular Cross Sections

A solid with triangular cross sections is formed when a region in the plane (called the base region) is paired with a description of how a triangle is drawn perpendicular to an axis at every value of the input variable. The triangles change size smoothly depending on the width of the region at each point, producing a three-dimensional solid when accumulated.

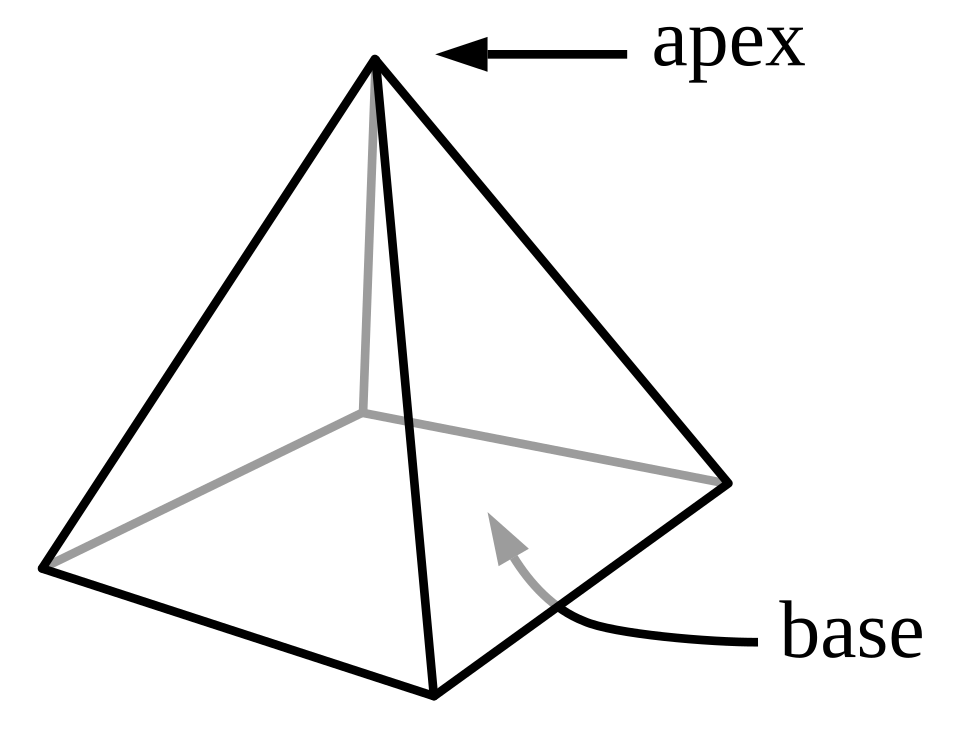

A labeled pyramid illustrates how triangular faces define a three-dimensional geometric solid. This helps visualize how varying triangular slices can accumulate to form a full volume. The diagram contains only geometric labels and no extra calculus notation. Source.

When first discussing the base region, it is essential to recognize that this region determines the base length of each triangular slice. The base length refers to the horizontal or vertical dimension taken from the boundaries of the region and used to define the size of every cross-sectional triangle.

Base Length: The dimension taken from the boundaries of a base region that determines the side length or base of each triangular cross section.

Because AP Calculus AB frames volume as accumulated area, triangular cross sections naturally extend the idea of integrating area formulas over an interval. Each triangular slice is treated as an infinitesimally thin region whose area contributes to the total volume.

Using Triangle Area Formulas in Volume Problems

To find the area of each triangular slice, students must select the correct triangle area formula depending on how the triangle is defined in the problem.

Triangle Area Formula: A geometric rule giving the area of a triangle based on its measurable attributes, such as base and height or side lengths.

The most commonly used formula in this setting is the standard triangle area formula:

= Base length of the triangular cross section

= Height of the triangular cross section

Students rely on this formula when the cross sections are described as right triangles, isosceles triangles, or equilateral triangles, each having a relationship between side lengths and height.

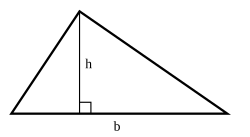

The labeled base and height clarify how the area formula is constructed. This parallels how triangular cross-sectional areas are defined before integrating to obtain volume. The diagram contains only essential geometric labeling. Source.

For example, if the problem specifies an equilateral triangle, its height can be written in terms of the side length using a geometric identity. If the triangle is a right triangle, the height may be equal to the given base or form a known ratio. AP problems may provide this relationship directly, or students may recall it from geometry.

Relating the Base Region to the Triangular Dimensions

The base region is typically bounded by curves or lines whose distance apart determines the dimension used in the triangle area formula. This dimension becomes the variable expression inserted into the area formula at each point along the axis of integration.

Students must determine whether the width of the region is more naturally expressed as a function of or of . This choice dictates whether cross sections are taken perpendicular to the x-axis or y-axis. The selection does not change the underlying strategy but ensures the integral uses a consistent and correctly oriented variable.

A typical problem will specify that the triangular cross sections are perpendicular to an axis. This description indicates how each slice is positioned and clarifies which variable serves as the input for the area function.

Cross Section: A two-dimensional slice of a solid formed by intersecting it with a plane perpendicular to an axis.

The cross-sectional area depends entirely on how the base region’s boundaries determine the side length inserted into the triangle's area formula. Once this relationship is established, the volume comes from integrating this area across the interval that describes the solid's extent.

Setting Up the Volume Integral

Once the area of a triangle at position or is known, the total volume is found by integrating these areas over the appropriate interval. The definite integral represents the accumulation of all triangular slices.

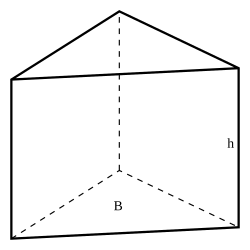

The triangular prism demonstrates volume as accumulated cross-sectional area, with constant triangular slices of area extended through height . This supports the AP concept of volume as an accumulation of area. Only the geometric quantities and are displayed, with no additional notation. Source.

= Volume of the solid

= Cross-sectional area as a function of

= Interval over which cross sections are taken

This expression emphasizes that the volume is built by summing infinitely many triangular cross sections whose areas vary with the input variable. Students interpret this integral as an accumulation of areas, consistent with the broader AP theme of viewing integrals as tools for combining infinitely many contributions of changing quantities.

Because triangular cross sections can take various forms in applied contexts, the formula for often changes depending on the type of triangle and how its dimensions relate to the base region. Regardless of the specific triangle, the fundamental strategy remains constant: express the triangular area in terms of the relevant variable, and integrate over the interval describing the solid.

Conceptual Interpretation in the AP Framework

This subsubtopic reinforces the broader AP Calculus AB principle that volume represents accumulated area, where geometric formulas interact with integration. Students learn to link geometric reasoning with calculus methods, translating a changing cross-sectional dimension into a function that becomes part of a definite integral. This synthesis of geometry and calculus highlights how three-dimensional quantities arise when two-dimensional shapes vary smoothly along an interval.

FAQ

Choose the axis that makes the side length of each triangle easiest to express. If the width of the base region is naturally written as a function of x, work with cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis.

If the boundary curves give simpler expressions in terms of y, choose the y-axis instead.

A good check is whether the resulting area expression depends on only one variable without needing to break the region into multiple intervals.

You may see:

• Right triangles with a given relationship between base and height.

• Isosceles triangles where the leg or base is determined by the region’s width.

• Equilateral triangles, in which the side length directly determines the height using geometry.

The exam typically specifies the triangle type so that you can apply the corresponding geometric formula.

Triangular area depends on more than a single dimension. For many triangles, only one dimension comes from the base region, while the other must be obtained using geometry.

Recognising these relationships ensures the area is expressed correctly before integration, avoiding errors that lead to incorrect volumes.

Yes, but only when the dimension that determines the triangle’s side length changes form across the interval.

This occurs when:

• The base region boundaries switch from one dominating curve to another.

• The width of the region is defined by different expressions on different subintervals.

In such cases, set up separate integrals and sum their results.

Useful checks include:

• Confirm the area function is always non-negative across the integration interval.

• Estimate whether the cross sections are getting larger or smaller and ensure the integral reflects that trend.

• Compare the final volume with a simpler bounding solid, such as a rectangular prism, to see whether the result falls within a plausible range.

These strategies help identify algebraic or geometric errors before concluding.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has a base on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 4 along the x-axis. At each value of x, the cross section perpendicular to the x-axis is an equilateral triangle whose side length is given by s(x) = 2 + x.

Find the volume of the solid.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies that the area of each equilateral triangle is A(x) = (sqrt(3) / 4) [s(x)]^2.

• 1 mark: Substitutes s(x) = 2 + x to obtain A(x) = (sqrt(3) / 4) (2 + x)^2.

• 1 mark: Integrates A(x) from x = 0 to x = 4 to obtain the correct volume.

Total: 3 marks

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies that the area of each equilateral triangle is A(x) = (sqrt(3) / 4) [s(x)]^2.

• 1 mark: Substitutes s(x) = 2 + x to obtain A(x) = (sqrt(3) / 4) (2 + x)^2.

• 1 mark: Integrates A(x) from x = 0 to x = 4 to obtain the correct volume.

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1 mark: Notes that the base length of each triangular cross section is 6.

• 1 mark: Recognises that the height is twice the base, so height = 12.

• 1 mark: Writes the area of a right triangle: A(y) = (1/2)(6)(12) = 36.

• 1 mark: Sets up the integral V = ∫ from y = 0 to 3 of 36 dy.

• 1 mark: Evaluates the integral to obtain 108.

• 1 mark: States the correct units (cubic units).

Total: 6 marks